Lehre

Wintersemester 2024/25

Prof. Dr. Andrew Monson: "Three Kings: Alexander, Ashoka, and Zheng", Hauptseminar

Wednesday, 14:00-16:00 (Residenz 3.37)

Inhalt:

In this course we compare three kings whose legacies have shaped the theory and practice of monarchy and empire in Eurasia through the ages: Alexander of Macedon (338-323); Ashoka of Mauryan India (c. 268-232), and Zheng of Qin, First Emperor of China (247-210). We examine contemporary evidence, including texts and images produced or authorized by them, as well as the posthumous historiographical and philosophical traditions. In addition to the historical reliability of these sources, we discuss the challenge that such powerful individuals pose to conceptions of sovereignty, legitimacy, humanity, and divinity.

Literatur:

- Hans-Ulrich Wiemer, Alexander der Große (C. H. Beck), München, 2015.

- Patrick Olivelle, Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King (Yale University Press), New Haven, 2024.

- Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, The Many Lives of the First Emperor of China (University of Washington Press), Seattle, 2022.

Prof. Dr. Andrew Monson: "City-States in Comparative Perspective", Theorie und Methode (Übung)

Donnerstag, 10:00-12:00 (Philosophiegebäude, TBD)

Inhalt:

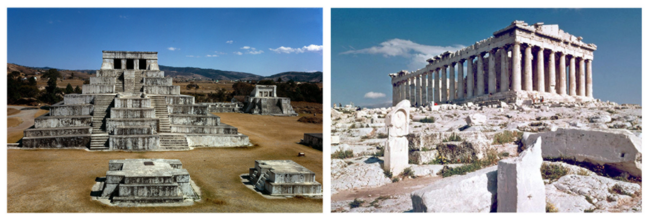

City-states emerged in different world regions independently, often forming clusters known as city-state cultures with similar customs, language, and religion. We will read a variety of case studies from premodern societies in East and West Asia, Africa, America, and Europe. Our emphasis will be on urbanism and state formation, economic and political institutions, and resistance to hegemonic-imperial domination.

Literatur:

- Deborah Nichols and Thomas Charlton, eds. The Archaeology of City-States: Cross-Cultural Approaches, Washington, 1997.

- Mogens H. Hansen, ed. A Comparative Study of Thirty City-State Cultures, Copenhagen, 2000.

- Tom Scott, The City-State in Europe, 1000-1600: Hinterland, Territory, Region, Oxford, 2012.

- John Ma, Polis: A New History of the Ancient Greek City-State from the Early Iron Age to the End of Antiquity, Princeton, 2024.

Prof. Dr. Andrew Monson: "Approaches to World History", Theorie und Methode (Übung)

Montag, 10:00-12:00 (Philosophiegebäude, TBD)

Inhalt:

World history is as old as history writing itself but was pushed to the margins as the discipline was institutionalized in the nineteenth century. Since then, research and teaching has been organized around the histories of nation-states or the culture-histories of pre-national peoples. In the past decades, however, globalization has turned global history into one of the most important subfields within the discipline. This course will introduce its goals and methods through reading works by prominent contemporary proponents. We will discuss the relationship between globalist and comparativist approaches, between world history and area studies, and between world regions in history.

Literatur:

- Birgit Schäbler, ed. Area Studies und die Welt: Weltregionen und neue Globalgeschichte, Wien, 2007.

- Jerry H. Bentley, ed. The Oxford Handbook of World History, Oxford, 2011.

- Sebastian Conrad, Globalgeschichte: Eine Einführung, München, 2013 (English: What Is Global History? Princeton, 2016).

Dr. Xiang Li: Public Communication in Late Antique China

Montag 14:00-16:00 (Philosophiegebäude, TBD)

The nature of “Late Antiquity” has been contested. Scholars of Roman history have used a series of dichotomous metaphors to portray the contradictory components prevalent in society during this period: “secular” and “spiritual,” “imperial” and “provincial,” “public” and “private,” “unification” and “division,” “isolation” and “interaction,” and so forth. Historians who focus on other parts of the world have largely accepted these binary narratives. One problem inherent in such models is that, by distinguishing between two seemingly incompatible status, researchers imply that individuals in Late Antiquity always faced severe splits in their real lives and were constantly troubled by paradoxical elements, without having any healthy daily routines. Another issue with these distinctions is their treatment of new social phenomena as completely subversive, thoroughly opposing existing norms and conventions. Studies on traditional China could help us transcend this binary model of interpretation. Though facing chaos, many people survived crises by sustaining a certain order, putting their desires and ambitions into words, and enjoying pleasures from the deepest part of their minds. This course explores how to locate the territory that we call “China” within the historical context of Global Late Antiquity (ca. 100s–500s), and how to redefine “Late Antiquity” from the perspective of China studies. We focus in particular on two activities that shaped the image of Late Antique China by influencing people’s conception of basic human relations: the expression of thoughts and feelings, and the exchange of ideas or things. The flourishing of both activities contributed to the making of a new society that was largely founded upon techniques and ethics of public communication.